Submarines are in the news these days as UK political parties continue to debate the whys and wherefores of renewing the Trident nuclear deterrent vessels.

No such shilly-shallying happened during the Second World War, evidenced by top secret operations which took place in a number of localities up and down the west cast of Scotland.

In an effort to protect Allied shipping, the Government in the early 1940s, ordered the training and preparation of human torpedoes and midget submarines in remote sea lochs.

Security was tight because of the nature of these activities and of the equipment being trialled. Only bona fide residents and military personnel were able to come and go, and even they needed the most up-to-date coloured passes.

The Morvern Peninsula was one such ‘Protected Area’, with sentry boxes at the top of the slipways on either side of the Corran Narrows and 24-hour check-points manned by armed-soldiers on the approach roads.

As an example of how seriously the military monitored and regulated the movement of people, animals and goods, is a story told of a Glasgow undertaker returning a body to the peninsula for burial who was forbidden to take his hearse onto the ferry because he did not have the correct paperwork. He was ordered to report to the nearest command post to obtain clearance and was told that if he returned without it a bullet would be put through the side of the coffin to ensure there was no spy hiding inside!

On another occasion Arthur Strutt, the Kingairloch Estate owner, drove all the way up from his home in Derbyshire to find that the colour of the passes had been changed without his knowledge. There were no exceptions and he was forced to about turn and make the long journey back.

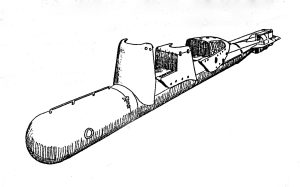

What was it that the Royal Navy were so anxious to protect in Morvern? The answer was a base in Loch a’ Choire entered from Loch Linnhe, experimenting with two-man, torpedo-like craft with detachable war-heads, known as Chariots and one-man midget submarines called Welmans.

Work on them had been carried out by the 12th Submarine Flotilla in Loch Erisort on Lewis in 1942 but the weather, communications and getting supplies there all combined to force the RN to move the entire operation to the more sheltered inlet of Kingairloch (Port HHX) the following year.

In 1914, the Germany submarine fleet had 16 commissioned vessels. By the end of the war this had risen to 390 and of these 178 were lost in action. The early boats were fitted with kerosene engines giving them a surface distance upwards of 3,400 miles. Soon diesel replaced kerosene, extending their range to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic coast of America. At first these U-boats arrived in the Irish Sea and the Hebrides, often by way of the south of England. As the war escalated, however, this route became difficult due to the extensive nets and mine fields in the English Channel, forcing them to travel round the North of Scotland.

According to an article which appeared in Islay and Jura’s newspaper, the Ileach (July 3, 2009), and another published in Scottish Field slightly later, a First World War German U-boat used to hide away in a remote little bay called Clas Uig on the south-east side of Islay where its crew went ashore to shoot sheep, and to which its commander returned on holiday years after the Second World War.

Similar stories were told of these clandestine landings on the NW coasts of Jura, Kerrera and at Killundine in Morvern. Doubtless there were many more. The desire for fresh meat appears to have been great. Fresh food was a major problem for patrolling U-boats. Johannes Spiess, commander of U19, in his book, Seven Years in a U-boat, recorded that some of his men landed on St Kilda and North Rona to shoot sheep to provide fresh mutton for his crew. Others gathered seabirds’ eggs to supplement their tedious diet of canned food.

There is a headstone in Kilbrandon church yard near Balvicar on the Island of Seil, recording the death of Neil McDougall Morton, from Sutherland, aged 27 years, chief officer of the SS Belgian Prince who was washed ashore at Cuan Ferry. Erected by his mother, it tells us that her son was ‘torpedoed and cruelly murdered by the Hun’, on July 31, 1917. If you think there is something unforgiving about the inscription read on.

The Belgian Prince was attacked by U-55, off the north west coast of Ireland. The torpedo did not immediately sink her allowing all aboard to get into the lifeboats and row across to the submarine. Her captain was taken below while his crew were lined up on the submarine’s hull. Their life-jackets and outer-clothing were removed by the Germans who proceeded to destroy the lifeboats. After sinking the stricken ship with its gun, the submarine submerged, deliberately washing the Belgian Prince’s crew into the sea. Without lifejackets they had little chance of surviving and all but three were drowned. Those who managed to stay afloat were picked up by a British patrol 11 hours later. It was an act of cold-blooded murder and completely against the 1907 Hague Convention.

At Kingairloch the base was centred round HMS Titania, an old-fashioned looking First World War depot ship, known affectionately by all who served on her as ‘Tiddly Tites’. She was anchored fore and aft to a massive bronze cable in the centre of the loch. It was ideal. Shallow at one end and deep at the entrance where two massive, anti-submarine and torpedo wire nets were suspended five to six fathoms below the surface to protect the base and on which divers trained during the hours of darkness.

In charge of the operation was Commander W R Fell CBE DSC RN who, along with his wife, befriended Mrs Emily Strutt, widow of George Herbert Strutt, the Derbyshire Cotton magnate and proprietor of Kingairloch, who purchased the estate in 1902. The arrival of this top-secret project in the loch brought with it many problems for local residents. Their letters were censored, their activities restricted to the estate – unless they had special permission to leave. No cameras were permitted.

Initially there was some resentment to the intrusion and the strict security issues but it quickly disappeared when the Navy helped out with rations, provided farm labour and even established a field telephone line from HMS Titania to Kingairloch House. In return the sailors were allowed to go ashore to stalk on the surrounding deer forest receiving plentiful supplies of fresh venison and fruit and vegetables during the winter months.

One of Mrs Strutt’s daughters recalls her mother was so patriotic and war conscious she wouldn’t even look in the direction of the loch in case she saw something she wasn’t supposed to know about. Mrs Strutt was obsessed with the thought of a Nazi invasion that she kept a large bottle of poison in the strong room and sent word round her employees telling them that should the enemy arrive they were to come to the house where she would give them a spoonful to prevent them from being captured and tortured. After the war the bottle was sealed inside a heavy lead box, rowed out into the middle of the loch by Donald MacDougall the head stalker, and dumped overboard.

Thanks to the operation at Kingairloch many hundreds of enemy ships were sunk. One of the most famous was the disabling of the Tirpitz [42,900 tons] Germany’s largest battleship, in a Norwegian fjord leading ultimately to her being sunk by the RAF and the Fleet Air Arm in November 1944.

Amongst the mini-submersibles developed in the Second World War was a type of underwater canoe called a Sleeping Beauty. Twelve feet long and driven by an electric motor, these, too, underwent sea trials in Loch a’ Choire before being shipped out to the Far East for use against the Japanese. On one exercise 15 of them had to be scuttled and all the crew involved were captured and executed.

There is little evidence of wartime activities to be seen above the surface of Loch a’ Choire today except for a few massive chains and the rusting remnants of the practice nets, as well as a large corrugated shed that housed the ship’s laundry and still stands near the walled garden.

It would be a graceful act on the part of the Royal Navy if they would consider putting up a cairn on the loch side in memory of the charioteers and submariners who lost their lives developing and operating these unique and dangerous craft.